To the people who don’t believe racism is a public health threat

Over the past several months, several states and municipalities have declared racism a public health crisis. While it remains to be seen if these statements — which highlight the coronavirus, police brutality, environmental health risks, and more — amount in funding and more than soothing rhetoric, racism is a blistering and very real paradigm that oozes into every aspect of American life. It's role in public health has long been evident and was outlined in the 1985 Heckler Report, which found striking inequalities in infant mortality, cancer, strokes, and other health outcomes.

Whether through force, deprivation, or discrimination, racism kills.

Racism is a social construct that assigns value and hierarchy based on the interpretation of the color of one's skin. It is a system structuring opportunities unfairly disadvantaging some individuals or communities, and unfairly favors others. When public health talks about the intersection of racism and health, most think of interpersonal racism, which are acts of bias between individuals or overt prejudice.

The most common understanding of racism in our country can certainly impact health if, for example, a doctor refuses to administer life-saving treatment because of a patient's race. We're working to prevent a more fundamental and invisible fluid leaking from a deep wound of systemic inequities. Redlining, underinvested schools, precarious employment, and scarce access to quality healthcare. All are the interplay of a host of historic and ongoing institutional forces, shaping inequality in American society.

Perhaps what makes racism less accessible, as a critical cause of poor health outcomes, is because many people still believe in a "race gene" that makes some groups more susceptible in a biological way. We've mapped the human genome and found there's no basis for biological sub-speciation. If anything, it further exposes that race is a social construct.

Or perhaps, it's the belief that those affected should simply change their behaviors and will longer have chronic health conditions. This tendency toward behaviorist interventions have proven impractical for many, or only sustainable for short periods, at best. It also doesn't consider how and why the health disparities occurred in the first place.

Absolutely, we all should be physically active most days of the week, eating a diet rich in whole grains, fruits and vegetables. But it becomes harder to prioritize this when you don't feel safe in your neighborhood, or aren't paid a living wage and can't afford to buy healthy food to eat. Besides, racism goes beyond socioeconomic status. Black women in the U.S. are almost four times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than white women. This inequity is seen among black women who have college degrees and more.

The physiological impacts of racism on health is a proven scientific concept, and like every public health threat or epidemic, causes more disease, injury, or other poor health conditions than expected to occur among specific groups during a specific period. Numerous studies have found racism to be associated with unhealthy changes to key biologic systems which take their outsized toll on communities of color over time. Repeated exposure to racial prejudice and discrimination have been linked to poor mental and physical health such as chronic stress, high blood pressure, infections and diabetes.

So how do we prevent racism from being embedded in the body?

Public health investigators use a tool to help research and combat disease known as the epidemiological triangle. We've identified the external agent, the susceptible host, and the environment that supports the transmission of the agent to the host.

Whether we use a triangle or model that diagrams a pie of multiple causes, public health prevention requires we disrupt the pathways to disease. It requires we examine things outside of the doctor's office making some people sick and keeping others well. It requires we acknowledge and heal the centuries-old trauma of Native American dispossession, slavery, Jim Crow, Mexican land changing hands, internment camps, and other legacies that perpetuate racial inequity.

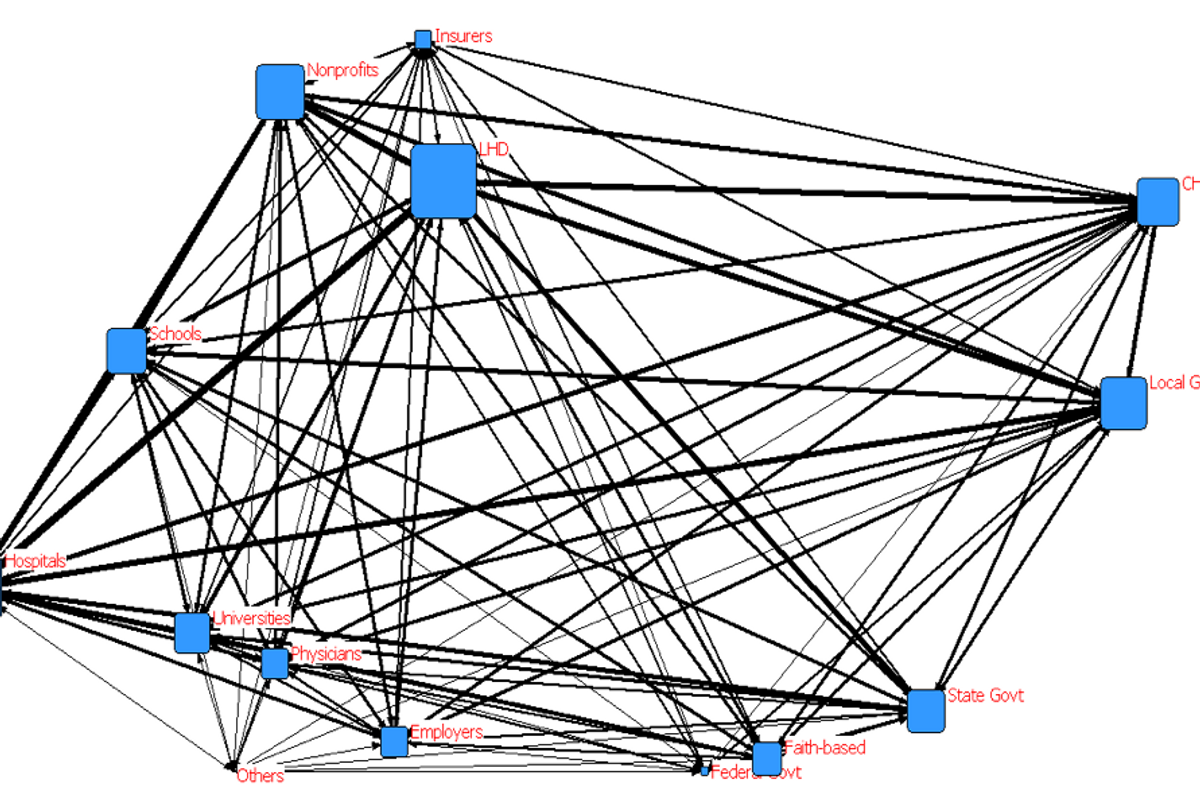

It requires sustained action across a variety of sectors, programs, and policies.

We must provide more access to economic opportunities, educational resources, and safe environments. We must get rid of the belief of limited goods that other groups deserve less so one group can have more. Our society has advanced when all members are meaningfully engaged and can contribute. When we allocate resources to the populations most impacted, every person in every community has an opportunity to be free from threats to their health.

Most importantly, we must shore up our public health workforce, training, equipment, data and communication systems. We cannot claim to be committed to the health of our nation if only 51% percent of the U.S. population is served by a comprehensive local public health system.

We only provide our public health infrastructure the funding it needs during an emergency, leaving our country to play catch up when the next arises. The estimated gap in the funding level required to ensure everyone is protected by a robust public health system is only about $13 per person. If we're losing lives, services, and a global competitive advantage, it's a price tag we can't afford.

Preventing death and disease in the United States means addressing racism as a driver of health inequities. This approach recognizes different races are situated differently across structures of society, and unless things change, there will be dire consequences for the changing face of our nation.Regina Davis Moss is the Associate Executive Director of Public Health Policy and Practice for the American Public Health Association, where she oversees the Center for Public Health Policy; Center for Professional Development, Public Health Systems and Partnerships; and Center for School, Health and Education.